In my previous post, we explored how Japan is utilizing a high percentage of RAP resulting in high quality asphalt pavements with optimized life-cycle cost, in stark contrast to the US.

The Solution is Obvious

Notice that none of these improvements to the way that RAP is utilized in the US are very complex nor should failure to address any of them be a reason for restricting RAP usage and performance. In fact, many might refer to these RAP improvements as “obvious.” It would be a game-changer for our infrastructure, so, why aren’t we doing “obvious”? I believe the fact that obvious solutions haven’t been more widely implemented in the US can partially be blamed on the inferior low-bid environment combined with a governmental approach that stifles innovation.

Given that road-building warranties are typically either non-existent or very short (2 years or less), what is the motivation to improve RAP performance or any asphalt pavement performance? In the US, the cheapest INITIAL offering meeting minimum specification requirements wins the bid. Yet the minimum requirements are not correlated to long-term performance. If they were, we’d have long warranty periods, and the specifications would ensure warranties were met, right?

Look no further than the interlayer bonding issue—talk about an easy and obvious solution to a major cause of premature failure—yet we continue doing it the wrong way. If a superior way to build roads is invented, by definition, the invention would be MUCH BETTER than the minimum specification requirement.

In this case, Japan has methods, which yield superior RAP performance. We have the technology and capability to do the same. Therefore, the agency must respond by increasing the minimum standard for RAP performance in the US. If they do not, inferior roadways are what we will continue to get. In Japan, the best life-cycle cost wins the bid. Japan’s approach nearly mirrors that of public private partnerships (PPP’s) here in the US and abroad. It is interesting how PPP’s mandate warranties and maintenance contracts as part of the construction contract, and magically, that leads them to superior materials, methods, and technologies which cause the roadways to perform better and last longer. How do I know this? Because we have a history of supplying products to PPP’s. Life cycle cost is what they are after, and that’s what we deliver.

The Lowest Bid System Stifles Innovation

I will close with an example of what typically happens in the US with a focus on cheap rather than life cycle cost.

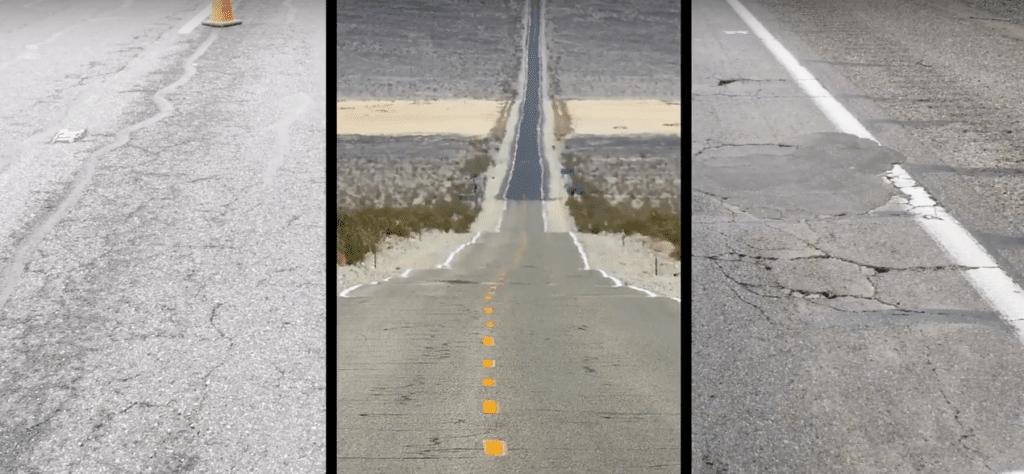

The DOT accepts the lowest (cheapest) initial bid, and when it is later discovered that something fails prematurely, a ban or restriction of the thing that may have caused the failure typically follows. Take RAP, for example. There have been periods in recent US history where much higher RAP content was approved by D.O.T.’s and even attempted with little success. What happened next? The DOT responded by placing a lower maximum restriction on allowable RAP content or by requiring additional virgin binder in mixtures containing RAP. Neither of these reactions to higher RAP content acknowledges why higher RAP content didn’t work in the US while it is working in places like Japan.

Why did it not work in the US? Because the objective was: INITIALLY CHEAP. The minimum specification requirements were never properly correlated to life cycle cost. There is no long-term warranty or expectation. Proof: the properties of the RAP binder are not even required to be measured per specification! This is too big of an unknown variable to enable a life cycle cost prediction.

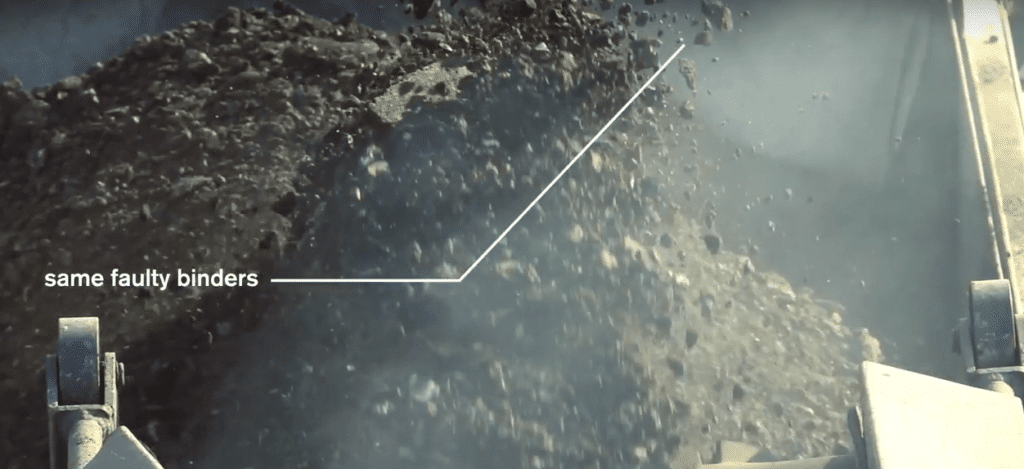

The problems I identified in my last post are not part of an INITIALLY CHEAP strategy, because there are cheaper ways to meet the specification; innovation period is not part of such a strategy. According to the initially cheap strategy, it is in the interest of every supplier and mix contractor to cheapen the materials as much as possible (as long as they still meet specification, which is often easy). So, the definition of innovation in an environment such as this becomes: who can find the cheapest junk to throw into the binder and mix to win the low bid without anyone noticing how bad the stuff really is.

Demand innovation from industry, and the demand will be met. However, don’t forget to upgrade specifications to accommodate proven technologies that make building great roads easy. This is the life-cycle cost approach. Change the bid environment to utilize innovative products and optimized life cycle cost will explode! Roadways MUST last longer, and we already know how to do it in so many areas. However, it will only happen if construction best practices are strictly enforced and available superior materials are in high demand by agencies. Let’s make a major impact now by improving our RAP.